There have been both local and international efforts to invest in the fishing industry, but most of these projects did not take off due to lower demand for fish, culturally Somalis prefer livestock. Nonetheless, fish diet is becoming more acceptable in urban areas, as climate change is pushing this desert state into finishing. Somaliland has a comparative advantage to export fish stocks to neighboring, landlocked East African countries.

The Somaliland National Development Plan projected that by 2021 the tuna fish harvest will increase by 20% due to an increase in demand for fish stocks from urban areas. Despite the projected increase in demand, the industry has few challenges to address before any growth.

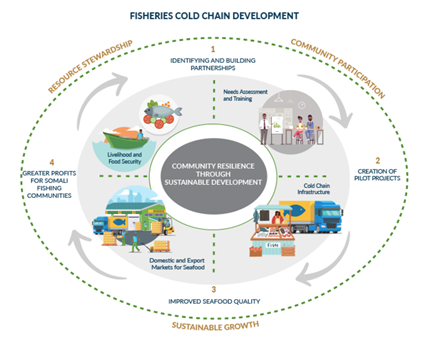

The cold chain infrastructure is barely non-existent at the moment. This makes it challenging for the fish stocks to be marketed and sold across Somaliland. Cold chain development is essential in reducing food losses and improving food quality in the fishing industry. Low access to ice and cold storage often result in fish being spoiled before reaching the market. Improving the cold chain infrastructure would immediately benefit fishers, processors, and others involved in the sector.

Regarding infrastructural challenges, there are many limitations to consider throughout the fishing supply chain. For instance, the quantity of appropriate boats is very limited, which affects the number of fish that are caught. Other challenges include the lack of appropriate storage facilities and nests. The lack of infrastructure for hygienically storing, processing, and transporting fish products is one of the major impediments to the development of the Somali domestic fishing industry.

There is no doubt that Somaliland has rich marine assets, but it lacks the appropriate infrastructure to fully leverage the industry. Currently, the unexploited fish stocks become vulnerable to piracy from neighboring countries and foreign fishing.

Somaliland’s marine life is abundant enough to be exported to neighboring, landlocked countries. For instance, Ethiopia imports fish stocks from China, Belgium, or Indonesia. This is a perfect example of Africa’s assets not being fully leveraged. Somaliland has a relative advantage in exporting fish stocks to mainland Africa. However, there are no processing facilities to produce and package the fish stocks.

The fishing industry is a highly profitable sector where the tuna industry alone is worth $6 billion globally. This is a market that Somaliland could easily tap into if the proper processing facilities are built. Investment in the marine sector would not only generate revenues but would create jobs for many unemployed youths in the coastal regions.

Furthermore, foreign investment is vital in expanding Somaliland’s fishing industry. UAE is a potential investor, as they are currently building the port of Berbera. UAE company, Dubai Port, already invested US$ 442 million to expand the port of Berbera, which is considered to be a strategic location for the UAE. However, foreign investment requires accurate data collection to evaluate and project the industry’s profits. Accurate data statistics play a crucial role in market analysis that is needed to attract potential investors. Another method of attracting foreign investors is significant tax incentives. The Somaliland government could offer a 0% tax rate for foreign investors during the first three years of operation or provide a 50% reduction on taxable profits. Both approaches have proven to attract foreign investors, which is a must if Somaliland wants to capitalize on its marine life.

Despite the structural challenges that have limited the potential of Somaliland’s blue economy, this is not a lost cause. In this article, we will also address a few recommendations that could dramatically change the outlook of the industry.

- Investment in Data and Knowledge

The most pressing challenge that Somaliland’s economy faces is the lack of scientific research and knowledge on its sectors. At the moment, there is a lack of concrete data on the diversity of the fish stocks, the conditions of commercially viable fish stocks, species under threat, and the overall ecosystem. In order to fully understand the potential of the fishing industry, it is imperative to have a thorough assessment of the sector. The government in collaborations with international organizations must commission institutions with adequate expertise to assess the status of the marine habitat around the country. International agencies such as the World Food Programme (WFP) could be particularly interested in providing expert analysis. The only way to improve the market value of the fish stocks is through improved market access and partnership with relevant investors and donors. Without data and comprehensive knowledge of the sector, potential donors will be less likely to invest.

2. Strengthen the Capacity of Local Institutions

It is no secret that Somaliland’s marine life is vulnerable to piracy and illegal exploitation from neighboring countries. Sometimes Yemeni fishers catch their fish stocks within the Somaliland borders. Recently, the Somaliland Coastal Guard arrested 81 Yemenis in six fishing boats near Berbera (northern coast) for unlicensed fishing.

These Coast guards need proper training, equipment, and better facilities to guard the marine borders. The Coast Guards are one of the weakest institutions that would greatly benefit from some sort of capacity-building. Illegal fishing in the Somali waters could threaten marine life and lead to overexploitation. In addition, the Somali coast has a bad reputation for piracy that has reached its peak in 2011. These piracy incidents have severe economic consequences as well as a poor public image that would push away investors and donors. In order for Somaliland to compete with international markets and export fish stocks to neighboring countries, it should put together a comprehensive strategy that would strengthen the capacity of the coastal guards and other relevant local institutions.

3. Development of Regulatory Policies across the Value Chain

Most of the fishing enterprises in Somaliland are informal – businesses that lack formal license registration and do not pay any taxes. Informality often leads to poor governance and low productivity. According to World Bank research, the average informal business in developing economies is only one-quarter as productive as the average firm operating in the formal sector. Therefore, Somaliland’s Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Tourism should put together a plan that would formalize the businesses in the fishing industry. In order for Somaliland’s blue economy to significantly contribute to the GDP, fishing businesses should all be formalized by including them in the formal tax and financial systems.

The Earth’s oceans have been a source of sustenance to the coastal population and generated income opportunities to millions. Seafood currently provides 17% of daily animal protein consumed globally, yet the blue economy is underexploited in Somaliland. In addition, over 1 billion people globally rely on seafood as their primary source of protein, which demonstrates the large, global demand for fish stocks. According to food security economists, seafood supplies for human consumption will need to increase by 70% due to population growth and economic development.

On the supply side, based on recent research, investors have approximately $5.6 billion in capital to invest over the next five years and dramatically shape the world’s blue economy. Lack of funding or finance is not a challenge, but connecting the donors to Somaliland’s abundance of marine life is the biggest obstacle. Hence, investment in data, knowledge, and sector analysis could provide valuable insights that could attract such investors. However, Somaliland cannot rely heavily on donor funding alone. The local institutions play an important role as well, in particular the coastal guards and regulatory institutions in charge of the formalization of businesses.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Deqa Aden is A Pearson Fellow and Masters in Public Policy (MPP) candidate at The University of Chicago and a member of the Somaliland Professionals Association of America (SLPA). She is an alumni of the Abaarso School, Grinnell College, The World Bank HQ in Washington DC where she was an Analyst and most recently Manager of Hargeisa Innovation Hub.

SLPA Website: myslpa.org

This article appeared in the Somaliland Chronicle and is republished with permission

Comments are closed.