China’s ban on the BBC within its territory hardly surprised anyone.

The action followed the UK’s decision to revoke CGTN’s license in early February for essentially being a Chinese state mouthpiece, and is mostly seen as a reprisal from the Chinese regime.

Due to the access of the BBC World News already being extremely limited in China, such a move has very little, if any, substantial impact on the country.

This may explain why the huge blow for the BBC, one of the most revered and trusted news outlets, only received lukewarm coverage from major newspapers and broadcasters, garnering mixed opinions under the comment section of the rebuttal tweet from the UK’s Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab.

China’s unexpected Allies

Whilst some others support the BBC for speaking out against truths that China doesn’t like to be heard, right-leaning Brits who are often at odds with the BBC’s narratives sarcastically claimed that the ‘Beeb’, as an outlet of government propaganda, should also be barred in its home country by using the hashtag #DefundTheBBC.

Similar things have happened as well around the globe as is seen on Twitter.

And the Chinese might find themselves receiving the strongest support from the most bizarre of allies given the two nations coming to the brink of all out war in mid-2020 – Indians.

A fair amount of loyal Indian supporters of the Modi government are complaining about “unfair reports” from the BBC surrounding the latest farmer protests in Delhi.

China, unsurprisingly in this manner enjoyed support from many Indians, although a majority of these netizens did admit to viewing hardly any BBC World News programming before.

Irregularities behind China’s regular retaliation.

The announcement was, bizarrely, made effective on the first day of the Lunar New Year, a timing when the general public hardly cares for anything but family reunions and celebration.

By the time of the next press conference of the Chinese Foreign Ministry scheduled for tomorrow – February 18th – the incident will likely be long forgotten and far from the public eye.

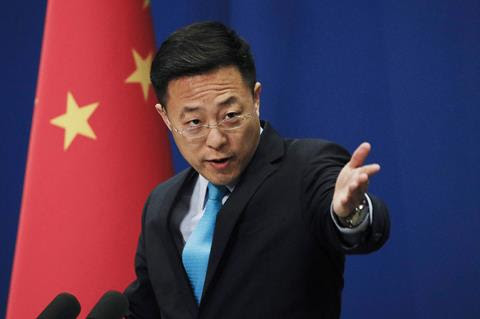

Secondly, the decision received little attention from that most vocal “wolf-warrior diplomats”– the spokesperson of China’s Foreign Ministry, and the controversial editor-in-chief of the Global Times, Hu Xijin.

That wasn’t the case when the bilateral tensions was intensifying in mid-January.

The two countries partook in several fierce skirmishes across different topics — the British National (Overseas) passports for Hong Kongers, the BBC’s exclusive report about Uyghur Muslims, the revoked license of China’s CGTN, all followed up by the retaliatory measures imposed by the Chinese in banning the BBC.

Refraining from all-out war

The series of events did not even include the usually sensitive topic of espionage – a story first published by the Daily Telegraph, in which it said that three Chinese intelligence officers were “quietly expelled” last year.

They had tried to hide their real identities as agents of China’s Ministry of State Security by playing themselves off as journalists.

In a statement from the Chinese Embassy, the spokesperson only used the word “spy” once in mentioning the headline of the news and circumventing the accusations by focusing on the “professional ethics” of Chinese journalists.

The two sides acted quite reservedly to avoid a potential all-out showdown similar to those seen of late between the US and China.

This evidence might imply both the UK and China are toning down the rhetoric surrounding the recent issues London and Beijing have been squabbling over.

And the ban of the BBC could potentially be a sign of a truce of sorts — at least in the short term.

Comments are closed.