Dear Editor:

China has long been known to the world as the most populous nation on earth.

This strength of ‘numbers’ helped China become a vibrant market for multi-national companies and western business enterprises.

It also allowed China to offer cheap labour to production and manufacturing units which helped China turn itself into a global production house.

However, this strength of numbers is projected to dwindle in the years ahead.

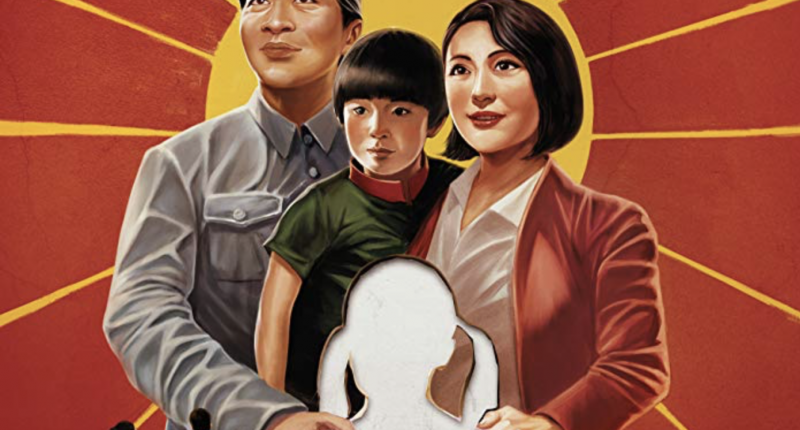

From 1950 to 1978, China’s population growth averaged 20% annually. Alarmed by the rising population, China enforced a one-child policy from 1979 to 2015, which resulted in China’s fertility rate falling from 2.8 children per woman in 1979, to 1.7 children per woman in 2014.

This decline in the birth rate coincided with governmental policies facilitating greater access to healthcare, as a result of which, life expectancy also improved from 67 to 75 in the same period.

These developments have set up a problem which the Chinese Government would have not expected just four decades ago.

China’s population is growing old at a faster rate than almost all other countries.

While it will take China 20 years for the proportion of the elderly population to double (2017-2037), this process took 23 years in Japan (1984-2007), 61 years in Germany (1951-2012), and 64 years in Sweden (1947-2011).

This demographic shift presents considerable social and economic challenges. The trend is particularly worrisome, as China’s future development and the sustenance of development are tied to its demographic advantages.

The number of Chinese retirees is projected to skyrocket, which will put further pressure on Chinese resources to support its senior citizens. Gauging these problems, provinces like Liaoning have proposed to allow a third child to married couples.

The challenge of an aging population: China’s fertility rate has fallen to below population replacement levels (the amount of births needed to sustain population size) at just 1.69 children per woman.

In order for a population to maintain its size, the total fertility rate must be around 2.1 children per woman.

The growth of economic activity in China has been reliant on affordable sources of labor, but the trend towards increasing an aging working population presents a serious economic problem.

As China’s large labour surplus pool begins to decline, daily wages are likely to increase which will have a serious impact on the profitability of business enterprises which in turn will affect China’s viability as a manufacturing hub.

Furthermore, the growing number of elderly retirees and shrinking pool of taxpayers will put significant financial strains on the government.

The percentage of Chinese people above the retirement age is expected to reach 39% of the population by 2050.

At that time, China’s dependency ratio (the number of people below 15 and above 65 divided by the total working population) is projected to increase to 69.7 percent, up from 36.6 percent in 2015.

This means that China will have a proportionally smaller working-age population with the responsibility of providing for both young and old.

The government would then need to play a larger role in strengthening the fledgling social welfare system and in improving China’s elderly-care capabilities.

Traditionally, Chinese culture involved the element of Chinese children taking care of their parents.

This cultural trend has resulted over the years in allocation of a smaller portion of government resources towards elderly care.

But now, there is often only a single child to take care of the parents as well as grandparents.

This problem has been further exacerbated by the growing trend of nuclear families and children migrating to cities in search of jobs. It is striking that an estimated 23% of the elderly in China cannot take care of themselves.

A large percentage of the aging population is not the beneficiary of the pension system, dependent on family members, who are also financially stressed, leading to social disharmony and resulting in increasing instances of suicide by the elderly or abuse of elderly by family members.

All these developments are leading to social tensions.

In contrast to earlier times when Chinese families had many children and they went into professions of their choosing families are now obliged to send their only child to perform national service in the PLA, much to the discomfort of the family.

Such grumblings have often been observed in Chinese social media depicting the level of rising societal discord in China.

Overall, China’s increasingly aging population threatens to rupture the social fabric of the country, and thus presents challenges in maintaining social stability even as it threatens to take off the sheen of the strength of the ‘numbers’ that China – at present – enjoys.

Gender Imbalance: The one child policy had its own perils. It contributed to a gender imbalance as rampant sex-selective abortions were undertaken to ensure that the only child was male.

As a result, between 1999 and 2013, around 71,600 children were given up for adoption to foster parents based in the U.S., of which 90% were female.

Further, it is estimated that there are over 62 million “missing” women (females who would be alive without gender discrimination) in China today.

In 2014, there were approximately 41 million more men than women in China, which is a factor with a high probability of contributing to social instability.

Additionally, the one-child policy invited lots of international criticism and accusations of human rights violations for enforcing forced abortion and sterilization by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres.

Anon.

Gujarat, India

Editor’s note: The Taiwan Times welcomes all letters to the editor, and all will be considered for publication. Anonymity will be respected after initial communication. Edits will only be made for clarity.

Comments are closed.