One of the main concerns of China’s one-party state is dissidence against the CCP and its spread in society.

Ever since Tiananmen Square in 1989, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has ensured that dissidents have remained under control, criticism restrained and if things get out of control the party purges such elements without too much fuss.

Many dissidents have settled abroad, while these days a number of dissidents like Xu Zhangrun have run the gauntlet inside China, knowing fully well that they run the risk of being targeted by the Chinese state.

In the case of Xu Zhangrun, this is precisely what happened in July 2020.

Another example of such activism is Wu Lebao, who is based in Australia, but has been a cyber-dissident.

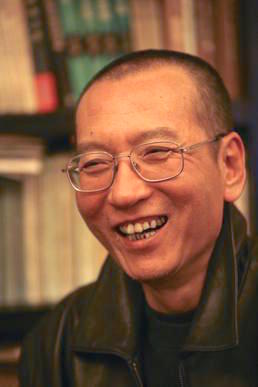

In 2019, Lebao was among one hundred or so dissidents, including Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaobo, whose name and works are totally forbidden in China, even in overseas publications.

Pertinently, the Chinese state today keeps tabs through electronic surveillance not only on its citizens inside China, but also those who have settled abroad making it easier for the state to monitor ‘dissent’.

Xu Zhangrun is perhaps today recognized as one of the leading voices of dissent in China, heavily criticizing the CCP and President Xi Jinping.

Xu wrote knowing fully well that at some point in time, the State apparatus would come knocking on his door.

The Beijing-based legal scholar, who worked at Tsinghua University till his arrest, had long anticipated such a day would come. Ironically, when the police came to arrest him charges pressed did not speak of his writings or criticism of President Xi.

Instead, he was reportedly accused of soliciting prostitutes—a charge commonly trumped-up against dissidents in China and one that Xu himself had previously warned would be used.

In late 2019, the CCP removed the phrase “freedom of thought” from the charters of several major universities, replacing it with language which insisted upon allegiance to the party. Xu was in a sense a dissident who sought reform in China, not a revolution like those who stood at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Still, his persistent writings and essays were seen as a threat to the CCP and its leader Xi, and therefore it was thought necessary to ‘fix’ him.

Michael Rowand writing in Foreign Policy aptly states: “Xu’s writings are critical of Chinese political power structures but always evince a care for the well-being of the Chinese nation.

It was this visible affection for his native land that allowed him to initially thrive as a scholar”.

Cai Xia, is a party insider who recently (August 2020) was expelled from the CCP for her comments on social media on President Xi.

Based in the US since last year, Cai Xia is a second generation communist whose parents had fought in the Communist revolution in 1949.

She retired from the CCP’s Central Party School where she had been teaching politics to party members who were being groomed for higher leadership.

The Central Party School is an important part of the CCP’s organization and it was led by Mao Tse Tung in the early days. There is a similarity and difference between the dissent shown by Cai Xia and Xu Zhangrun.

Both are insiders in one sense, though Cai was a deeper part of the system and her criticism of Xi is far more strident.

In fact, her comments on Xi are even being seen as a sign of the waning power of Xi and his CCP colleagues within China.

The very fact that the CCP expelled her from the party and stopped her retirement benefits indicates the crude attempt to stifle dissent.

In an interview with the Guardian newspaper (June 2020), Cai accused President Xi of making “the world an enemy” of China, and said he wanted to “consolidate his own position and authority.”

Her analysis of recent developments is that “Considering domestic economic and social tensions, as well as those in the party of the last few years, (Xi) will think of ways to divert the attention of the Chinese public, provoking conflict with other countries, for example encouraging anti-American sentiment and the recent clash between China and India,” Cai said.

The issue of dissidence in China and actions against them extends not only to Chinese citizens who criticize the CCP or President Xi.

Ethnic minorities in China including Tibetans and Uyghurs are also classified as ‘separatists’ and any individual who chooses to oppose the imposition of Han rule becomes a ‘dissident’.

Many overseas Chinese who have fled to democratic nations are silenced by state action against their families who are still in China.

For instance,in 2010, Liu Xia tried to travel to Oslo to accept the Nobel peace prize on behalf of her husband, Liu Xiabao, a human rights activist, who at that time was in prison for inciting protests in China.

Liu Xia was physically prevented from travelling and was placed under house arrest with 24-hour surveillance.

More recently, when the coronavirus pandemic hit Wuhan, a number of voices came up against the Chinese system and its failure to control the spread of the virus. One of them was Fang Fang who wrote the “Wuhan Diary”.

She was not the only one to vocalise the feeling that the Chinese state had failed in its main task of looking after the Chinese people.

There were others who went on social media, while still others like Ren Zhiqiang, a business tycoon and a CCP member, openly criticized Xi.

Ren has since disappeared.

As a keen China watcher and former foreign secretary, Vijay Gokhale writes: Ren Zhiqiang is ruthless in his attack on Xi Jinping’s attempts, post-facto, to ante-date his personal leadership in the crisis.

He derides Xi’s claims of having been on top of the situation in dealing with the pandemic since 7 January, and ridicules the Party’s unconditional endorsement of Xi’s successful leadership in a National Party Conference on 23 February, in these words: “Standing there was not some Emperor showing us his new clothes, but a clown with no clothes on who is still determined to play Emperor.”

As Lily Kau, reporting from Beijing wrote (The Guardian, 1 March 2020) episodes of public outrage are not uncommon in China, but criticism of the political system, which has become even more centralised under Xi Jinping, is normally rare among the public.

But the first three months of 2020, witnessed an unprecedented outpouring of anti-Xi/CCP sentiment.

Zhou Xueguang, a Professor at Stanford University, aptly summed up the situation thus in an interview, “This (handling of the coronavirus pandemic) is not only an outbreak of a novel virus; it’s also a manifestation of the breakdown of China’s governance structures,” he said. “The crisis has exposed the cracks in the system.”

The Human Rights Watch 2020 Report summarizes the Chinese State’s response to criticism from dissidents by noting that it has constructed an Orwellian high-tech surveillance state and a sophisticated internet censorship system to monitor and suppress public criticism.

China also uses its growing economic clout to silence critics (as in the case of the Uyghurs of Xinjiang) and carries out an intense attack on the global system for enforcing human rights. This then provides the underlying basis for the CCP’s crackdown on voices of dissent, which episodically rise, only to be suppressed by the Chinese surveillance state.

There is thus an increasing wave of voices that are pressing the CCP to remove President Xi from power.

The only problem is that these voices are those without support or an organization that can bring all these people together.

To understand the current situation, one has to perforce go back to the days of the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989.

One could recall Fang Lizhi’s open letter to Deng Xiaoping on 6 January 1989 demanding that all political prisoners in China be released as one such instance.

Recall that protesters at that time had been spurred on by the death of a leading politician, Hu Yaobang, who had overseen some of the economic and political changes.

China was also passing through a difficult economic period.

This led to mass demands for political change. The 1989 protests were led by students, and from 15 April to 4 June, the protesters besieged Tiananmen Square.

There is a clear signal here that President Xi is under pressure from his own people.

True, in the public mind, and from what can be seen in the open, Xi’s position is fairly strong and comfortable, but he faces an uncertain future what with the economy showing serious slowdown characteristics.

Seen in this context, the voices of dissent in China, be it mainstream or otherwise are indeed expressing concern over the increasing centralization seen under Xi, perhaps a symbol of the insecurity that plagues China.

Centralization driven by the use of technology to keep track of its citizens is therefore, the new mantra of the Chinese state and this will only intensify as President Xi struggles to keep his hold on power.

Comments are closed.