Editor’s Note: The following was submitted by Pitamber Kaushik of India; a journalist, columnist, writer, and independent researcher.

China’s ongoing spree of irresponsible conduct, misdeeds, uncooperative surreptitiousness and criminal neglect surrounding the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic did not commence in December of 2019, but rather its true beginning can be traced all the way back to 2003.

The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) occurred in November 2002 in Guangdong.

The Chinese government did not inform the World Health Organization until February 2003, despite the latter actively soliciting information from the former, after suspicion was aroused owing to detection by its Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network.

Guangdong SARS Link

In May 2003, samples from wild animals sold as food at a local market in Guangdong were studied. These studies showed that the coronavirus causing SARS could be isolated from masked palm civets even if the symptoms of the disease didn’t manifest in them or even without expressing any effects.

More than 10,000 palm civets were reportedly slaughtered in Guangdong. The virus was later also found in raccoon dogs, ferret badgers, and domestic cats, all of which are widely consumed in China.

In 2005, a couple of prominent studies discovered a number of SARS-like coronaviruses in Chinese bats.

In 2006, a clear genetic link between the coronavirus strains in civets and those in humans was established by Chinese scientists, lending strong credence to the hypothesis of the SARS outbreak being zoonotic in origin.

Wet Market Breeding Ground

In 2007, Guo-ping Zhao, a researcher at the Laboratory of Health and Disease Genomics, Chinese National Human Genome Center in Shanghai, wrote in a paper, “This SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) exploited opportunities provided by ‘wet markets’ in southern China to adapt to the palm civet and human.”

He explicitly mentions the facilitation that wet markets provide to the “animal-to-human jumping” of the virus and remarked on the role of the horseshoe bat as the transmitting agent, elaborating on the extent of the grave hazard that contact with wild animals posed to public health.

In retrospect, the eerily-foresighted titled paper “A SARS-Like Cluster of Circulating Bat Coronaviruses Shows Potential for Human Emergence” published in the leading scientific journal Nature expressed foreboding and concern over the same, in light of the SARS and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) outbreaks.

This paper also revised the previously held belief that a direct jump to humans was impossible and showed that little adaptation was needed. It also tested and affirmed the potency of hybrid virus infections.

Finally, in December 2017, 15 years after the SARS outbreak, researchers at none other than the Wuhan Institute of Virology zeroed in on viral strains found in horseshoe bats in a cave in Yunnan province that had all the structural makings of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

Living On Borrowed Time

The authors are quoted as stating that “another deadly outbreak of SARS could emerge at any time.” They highlighted the fact that the very cave where they discovered their strain was only a kilometer from the nearest village.

They reiterate and emphasize people contracting another SARS infection as a very definite possibility. Bats carry a host of coronaviruses, and studies have found a high probability of potential spillovers.

Undeterred by these myriad findings by both Chinese and foreign researchers, the earliest of them dating back to 2003, the sale and dietary consumption of all sorts of exotic wild animals ran rampant.

The pangolin is an animal that looks to have evolved for defense – it has perfectly arranged and oriented, close-packed overlapping tight scales all over its body as a lustrous coat of armor.

Moreover, when threatened, it promptly curls itself into a (veritably) impenetrable ball. Yet it has not escaped the gastronomic inclusion of Chinese cuisine, where it is considered a delicacy.

Most likely, SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus causing the current pandemic, crossed over the interspecies barrier from pangolins that contracted it from horseshoe-bat droppings.

China remains, by far, the largest market of illegal trade in wildlife.

Beijing also failed to learn from various zoonotic outbreaks since SARS, prominently Nipah and Ebola. In fact, 70% of emerging viral diseases represent zoonoses.

Yet “failing to learn a lesson” seems an ill-fitting description of China’s seemingly thickheaded apathy toward these potentially existential threats to humankind.

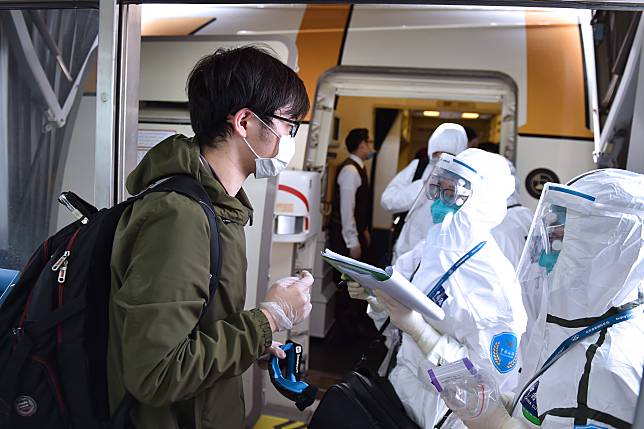

Wet Markets Reopened

China reopened its wet markets selling bats and pangolins, among other fauna crammed in cages and slaughtered in blood-soaked stalls, this time under the watchful eyes of guards who meticulously preclude any photography.

As long as wet markets abound with exotic bushmeat, umpteen infectious agents lurk right at our threshold.

The inertness and persistence of one particular kind of fondness or habituation continues to imperil humanity.

The lack of dietary compromise and government regulation – mostly motivated by folk medicine, pseudoscientific beliefs, and nouveau riche fads than survivalist necessity, nutritive content and value, or even epicurean considerations as actual salience of taste – shall ensure that the constant, glum threat of extermination constantly looms over humanity.